“There will never be another Beatles,” Gene Simmons once said. With every passing juncture of pop culture, that seems more and more apparent. There is an argument that there shouldn’t have even been a Beatles in the first place. They defied more of the norms of society than a cheese sandwich in China. It’s easy to reconcile their initial success, but for The Beatles to have sustained that as they ventured towards increasingly avant-garde avenues is a feat that flouts logic.

Yet, if you ask 100 people today to complete the sentence, ‘I am the egg man…’ a fair chunk will say, ‘goo-goo-cachoo’, whatever the hell that means. This not only proves the success of their experimentalism but also its transcendent and lasting impacts on society. This is a factor that most modern musicians have found pretty easy to compute. In fact, in our recurring quick-fire questions feature, we’ve asked hundreds of new bands if they consider The Beatles overrated, and no more than three have dared to deride the Fab Four.

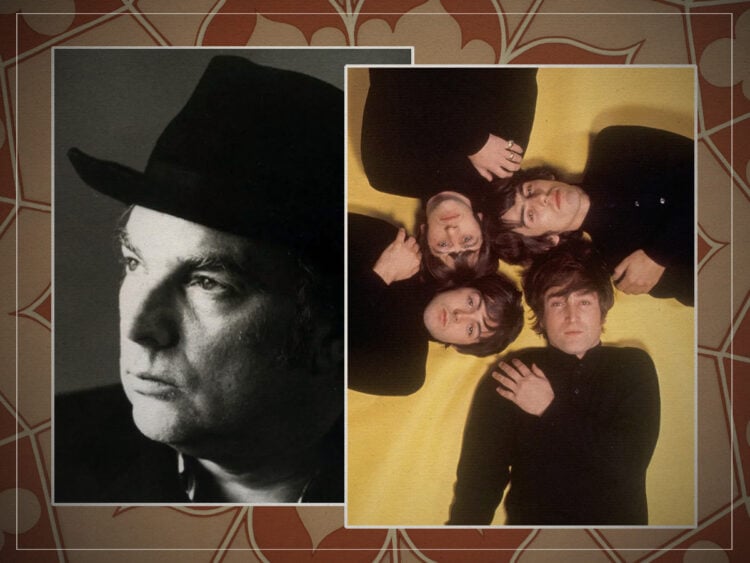

But back in their pomp, things were different. Ask any fan who saw them live after 1963 about how they sounded, and they’ll tell you that they couldn’t hear a single note over the screaming. So, in many ways, the music was riding in the backseat of the bandwagon. For folks like Van Morrison who had first been inspired by jazz virtuosos, this cacophony of teenbopper adulation did, indeed, seem to lack substance.

Thus, it comes as little surprise that the Astral Weeks singer slated the Liverpudlian group, cursing, “The Beatles were peripheral. If you had more knowledge about music, it didn’t really mean anything. To me, it was meaningless.” It’s a bold statement, but when Them first emerged in conjunction with the Fab Four and were met with a fraction of the fandom, his ire is at least understandable, especially considering that Morrison and his group probably were a lot more talented at that point.

Quincy Jones had a similar gripe, stating, “They were the worst musicians in the world. They were no-playing motherf***ers. Paul was the worst bass player I ever heard. And Ringo? Don’t even talk about it.” Once again, while this comment seems wildly over-the-top, for a fellow who initially made his name playing alongside some of the greatest American jazz musicians in history, the musical complexities of ‘She Loves You’ paled in comparison to the likes of Miles Davis at first.

Even George Martin, the so-called Fifth Beatle, who first unearthed the band as their producer, would agree. “So, they sent them down from Liverpool,” Martin recalled of his first meeting with The Beatles. “And when I listened to what they were doing, it was okay, but it wasn’t brilliant. It was okay, but I thought, ‘Why should I be interested in this?’” That’s hardly the mark of seismic, meaningful talents destined to set the world alight. In fact, it’s closer to Frank Zappa’s famed corroboration. “Everybody else thought they were God!” Zappa once snarled. “I think that was not correct. They were just a good commercial group.”

Morrison, Zappa, Jones, Lou Reed and everyone else who slammed the band as shams, however, were rivals in a very competitive musical scene. In their view, they were simply saying what they were seeing from the distant perspective of objective musical analysis. A degree of bitterness and jealousy no doubt comes into it, but there is equally no doubt that Morrison genuinely viewed ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ as a meaningless pursuit. He wasn’t a screaming teenager; he was a cynical Ornette Coleman fan tirelessly endeavouring to marry the melodicism of pop with the complexity of bebop. Caught up in the moment, criticism seemed inevitable.

However, it is the generation that followed who offered up the fairest assessment of The Beatles. They recognised that Beatlemania wasn’t a pointless tag-on to vapid pop, but rather a necessary driving force for societal liberation that we’re still reeling from today. And when The Beatles found themselves behind the wheel of this bandwagon, they steered in an increasingly progressive direction as their musicianship began to excel. By the close of the decade, they were a million miles from meaningless – if they ever were – McCartney’s bass playing was as complex as anyone’s, and to call something as radical as Revolver “commercial” would be incorrect.

As David Bowie, who found himself freed from competition with the group, trying to pick up from where they left off, put it regarding John Lennon, “I just thought he was the very best of what could be done with rock ‘n’ roll, and also ideas. I felt such akin to him in that he would rifle the avant-garde and look for ideas that were so on the outside of, on the periphery of what was the mainstream and then apply them in a functional manner to something that was considered popularist and make it work.”

Being popularist is important—someone has to satisfy the masses, so it may as well be a progressive and complex force rather than an implant imparting pop platitudes. As Leonard Bernstein, one of the era’s most ingenious composers, would also ratify, “For a long time now I’ve been fascinated by this strange and compelling scene called pop music,” Bernstein told CBS’ Inside Pop. “I say strange because it is unlike any scene I can think of in the history of all music.”

He wasn’t making music that competed in the same circle of ‘youth culture’, so he was happy to applaud it from afar. Speaking about The Beatles, the revered composer said that they were akin to Robert Schumann when it comes to ‘She’s Leaving Home’. “This new music is much more primitive in its harmonic language,” Bernstein adds, “It relies more on the simple triad, the basic harmony of folk music. Never forget that this music employs a highly limited musical vocabulary; limited harmonically, rhythmically, and melodically. But within that restricted language, all these new adventures are simply extraordinary. Only think of the sheer originality of a Beatles tune.”

As such, even the great Bernstein was affected by the anthems of the day; it brought inventiveness and curiosity to his canon, grounded forever, not just in the backbone of tempo, but how the simple waltz it led a generation through related to the substance of our lives at large.

It seems that often, what many of the naysayers scoff at when it comes to the Fab Four is figuratively (and sometimes literally), track one, side one, of the debut of four young working-class kids breaking through at the birth of pop culture—dismissing what they became, what they meant, and the advancement that they represented in every way.

Leave a Reply